New Creation Community

A Seventh-day Adventist Experience

Why Young People are Leaving Christianity and What We Can Do About It

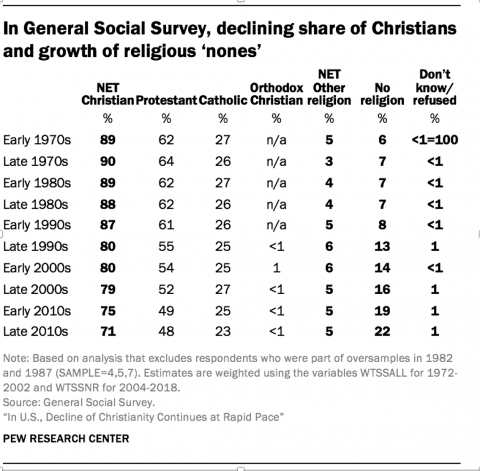

For most of America’s history, 80-95% of our population has claimed affiliation with some branch of Christianity. But since the 1960s, that number has plummeted to 70%. Even more alarming, people aren’t switching religions. People are leaving churches altogether. Secularism is on the rise. Worldwide, laws and societies are showing a growing intolerance for religion. The persecution of Christians doesn’t even make the news.

Article here

According to a comprehensive study on religiosity in America by researcher Lyman Stone published last spring, one of the key reasons for the rise in secularism has been government policy and political division. He sees the removal of school prayer as the largest contributor. Studies confirm the Biblical notion that the values and beliefs we teach our children stay with them into adulthood; in this case, people are about as religious as their parents. So banning religion in schools can have a lasting effect.

Stone may be on to something.

School prayer was banned in 1963 at a time when most of America claimed a Christian faith. This was a very unpopular decision by one Supreme Court judge and was predicated around the issue of keeping church and state separate. Some argued that constitutionally, separation merely aims to prohibit an official state religion that could become as oppressive as the Catholic or Anglican churches that the Pilgrims had fled from. Adventists themselves have long been strong proponents of this separation, possibly in the hope that we could delay or prevent the anti-Christ (even though the anti-Christ is said to be an “unholy trinity” of Catholic, Protestant, and Occult religions, and a world-wide power).

The ruling may have unintentionally started a cascade of secularism. Stone explains that for some students, school prayer had been their only exposure to anything religious. On the heels of the school prayer decision, civil rights, the feminist movement, and government social initiatives led to more entrenched poverty and skyrocketing divorce rates by the 1970s. Both parents began working, and single parents had less time to take kids to church, leaving more and more of their children’s education (moral or otherwise) up to schools and television. Over the years, schools have sought, in a gesture of “inclusivity” and “reason”, to exclude all religious mention from their curriculum, or at least caution students to its historic and scientific “errors.” As a result, consecutive generations grew up with less and less exposure to religious ideas or experiences.

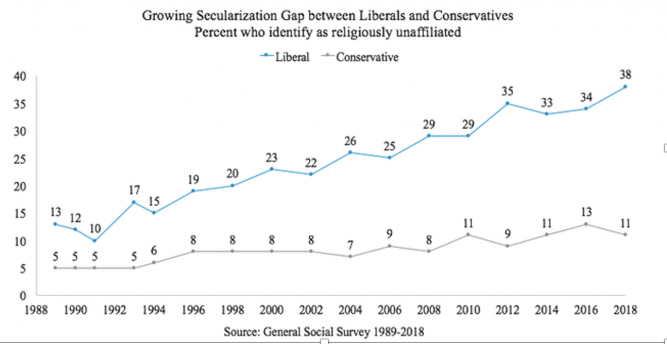

The next data spike in secularism hit in the 1990s, after two generations had experienced secular education and were now of average voting age. Politicians began taking laser-aim at polarizing voters (a sharp jump in “unaffiliated” on both sides spreads every election year, while the Moderate center has been steadily shifting Left). Although both political parties have equal numbers of Christians, criticism of the Christian Right creates a subtle perception that Christianity itself is the seat of social problems. Religious scandals have only added fuel to university anti-Establishment lectures that blame white Christianity for historic and current social ills, a notion that others have debunked.

Today, a full 40% of Millennials declare they are “unaffiliated” with a church, and 25% of those are turning to the occult to fill the spiritual gap. This generation grew up with an unprecedented number of tv shows about witches and demons, so it may not be surprising that they see astrology, Wicca, and even Voodoo as equal alternatives to Christianity, especially when popular culture openly mocks and slanders Christianity.

But the actual reasons people give for leaving their churches reveal a dissatisfaction that can’t be blamed on schools, parents, governments, or Buffy the Vampyre Slayer.

There are several studies[1] that polled all ages, but for brevity, we’ll look at the poll taken by the Barna Group that asked 18-29-year-olds why they’re leaving church:

-

Christianity feels stifling, fear-based and risk-averse.

- “Christians demonize everything outside of the church.”

- “My church ignores the problems of the real world.”

- “My church is too concerned that movies, music, and video games are harmful.”

-

Their experience of Christianity is shallow.

- “Church is boring.”

- “Faith is not relevant to my career or interests.”

- “The Bible is not taught clearly or often enough.”

- “God seems missing from my experience of church.”

-

Churches come across as antagonistic to science.

- “Churches are out of step with the scientific world we live in.”

- “I’m turned off by the creation-versus-evolution debate.”

- “I struggle to find ways of staying faithful to my beliefs and to a science-related career.”

-

The church’s views towards sexuality are often simplistic, judgmental.

- Many don’t know how to live up to the church’s expectations of sexual purity, especially as the age of first marriage is now commonly delayed to the late twenties.

- They say they “have made mistakes and feel judged in church because of them.”

- 40% of Catholic young people said the Church’s “teachings on sexuality and birth control are out of date.”

-

Christianity is exclusive.

- “Churches are afraid of the beliefs of other faiths.”

- “I feel forced to choose between my faith and my friends.”

- “Church is like a country club, only for insiders.”

-

The church feels unfriendly to those who doubt.

- “I don’t feel safe to ask my most pressing life questions in church.”

- “I have significant intellectual doubts about my faith.”

- “My faith does not help with depression or other emotional problems.”

The biggest problem, it seems, is less with Christianity’s message, than it is with its messengers (and Millennials may be voicing what older generations who also left the church were never asked). Christians either aren’t very Christian, or they aren’t sufficiently demonstrating the benefit of a spiritual life. Why can’t young people have their world and their religion too? It’s on us to make it clear that living for God is better than worldly values, otherwise what would compel anyone to try it? Too often we talk in religious jargon and abstract phrases that only make sense once someone’s experienced “the peace that passeth understanding” or “grace” or “sanctification” or the “power of the blood of the Lamb to overcome all unrighteousness.” Perhaps the greatest chasm for young people is with current issues around sexuality and science, topics we’ve either ignored or shrugged off with a pat, “because the Bible says so.”

The positive takeaway from all these studies is that we now have a better idea of what we need to do to retain our members and counter secularism.

- Apologies – When scandals happen in any organization, it’s best to admit wrong, apologize, and seek to rectify the situation. This should be the lesson all churches (and individuals) learn from the decades-long sex abuse scandal that not only rocked the Catholic church, but tainted all Christian faiths by association. However, as Jesus’ crucifixion showed, if you haven’t done anything wrong, never apologize to the mob. It only emboldens them and won’t help your case anyway.

- Apologetics & Apostles - Some churches have found that simply introducing apologetics to their church - defending and proving the truth of religious beliefs - helps retain younger members. Our youth have legitimate questions: Why is chastity better? How do we know the world is 6,000 years old? Does it matter that Christ was more than just a good man? Aren’t people all basically good, not evil? Aren’t all religions basically the same? How can a loving God send people to Hell? Explanations, however, are meaningless if the experience is missing. In a Christian Post article, Pastor Elizabeth Woning presents an excellent argument that the LGBTQ conflict with Christian beliefs on sexuality could be resolved by introducing them to Jesus (not the dogma of Jesus, but the experience of Jesus, the acceptance and community that LGBTQ - and all of us - fundamentally seek). Our Christian mission may have too long been centered on simply spreading the Good News, and not enough on developing relationships, either with God or each other. We must focus on the battle that’s most important, the inner, spiritual war we each face. And we must also build up our fellow soldiers in that good fight. Our first mission, above anything else, must be in securing that connection for ourselves because it’s transformative. The experience of Jesus is the foundation of what it means to be Christian; everything should flow from it. As we change, our relationship to other people changes. Spiritual growth ripples outward. We, Christ’s followers, are charged to follow His example and obtain perfection in ourselves, not demand it of others. As Biblical scholar William Barclay observed, “[t]he unanswerable argument for Christianity is Christian lives. No man can disregard a faith which is able to make bad men good.” Or, as Ghandi put it, “My life is my message.” We should each really ask ourselves what message our lives tell.

- Speak up – 1) If young people see God “missing” from the church, it may reveal a people problem, not a pulpit problem. It’s ok, in fact helpful, to talk about our spiritual journey. Do we show others how relevant God is to us? Do we talk about our personal struggles and doubts? Or our prayer life? Do we share stories of times when our faith got us through a crisis? If we’re hypocritical or judgmental, do we own up to it to the extent that others can see we aren’t perfect but that we’re working toward it? Why do we believe what we believe?

2) When one church is slandered, all faiths suffer. If we want to preserve religious freedom for all, we shouldn’t engage in mocking or slandering other faiths. And if others do, we need to stand up for all religions. Not every spiritual journey will follow the same path. We must trust that God is guiding people where they are – and we can learn from each other, regardless of affiliation.

3) We seem to be fumbling in a reversed Age of Enlightenment, where the religious are being persecuted for heresey against science. Too many scientists who are Christian remain silent about their beliefs in God or Creationism, lending to the perception that no credible scientist believes in either. Yet it’s increasingly difficult to have any conversation because even overheard speech can get one ridiculed, fired, cancelled or otherwise burned at the stake, even on private religious campuses. This only stops if we speak up.

- Seek up – To be fair, the polls also indicate some lack of effort on the part of those questioned. Priests, pastors, or parishioners can’t be solely expected to answer all our questions; each of us is growing in different ways and needs to explore the Biblical answers for ourselves, guided by earnest prayer. Christianity is more than showing up to church or acknowledging Christ as one’s savior. A relationship with God (like any) must be active, not passive. One has to seek God to find Him.

These studies are good news. Our society is by no means lost; they’re seeking answers. People may have become more secular, but they haven’t become less spiritual. The philosopher Peter Abelard once said, “By doubting we are led to questioning, by questioning we arrive at the truth.” Someone else put it more or less this way: Those who’ve never questioned have never fully believed. If people are doubting, it’s a step in the right direction. And if we haven’t asked the same questions ourselves, maybe we should start, and find answers--together.